Once more the new cuddly Conservatives reveal their twisted old Tory roots and hatred of universities. Unable to resist the chance of a pop at the seats of learning, the Home Secretary, her Shoeness Teresa May, manages to imply that it is universities most of all who are to blame for the alleged growth of radical extremist views within Islam.

From tabloids to Education ministers, the right wing have always hated intellectuals. For this cabinet, which has nursed its ideological fantasies since dewy-eyed schooldays, people who insist on rigorous scientific evidence for policy and hard work on figuring out the micro and macro economics of every decision, are particularly annoying. So irritating to have your lovely plan for the betterment of the human race sniped at by boring types who want to do pilot studies and point to sophisticated layers of social interaction instead of simple causes to problems. Let's ignore these wackos and Just Do It.

In an extraordinary move, then, the Home Secretary suggests universities are particularly to blame for not doing more to prevent the rise of right-wing extremist religious views on their campuses. Exactly what universities could do she leaves to our imagination. Should lecturers spy on their students - especially the darker-complexioned ones - and report anyone who seems to be a bit earnest about their Koranic knowledge? Chemistry departments should perhaps stop keeping an eye out for thefts of ethanol to fuel party animals, and instead undertake extensive inventories to ensure nitroglycerine is not being nicked? (Like they don't already!) Or should universities stop trying to be part of a commercial market economy, practice which has led highly regarded institutions like the LSE into accepting a bit too much money from Libya and awarding a very dubious postgraduate degree to Saif al-Islam Gaddafi. (Any such shift would need substantial support from a government which currently shows no sign of wishing to work towards a more transparent funding regime for Higher Education and research.)

Here's an idea. How about if universities be encouraged to provide an open public space for the debating of ideas. Then, Muslim students might learn to take up a diverse range of views and understand their own religious position as one among many in a multicultural society. This could be a way of getting young Muslim people to understand the rational thinking of the European Enlightenment and liberal values of the West.

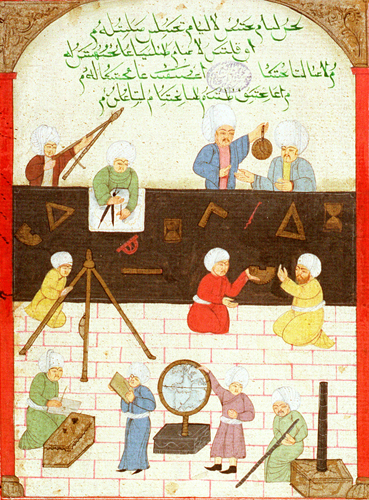

Oh, and we might even listen as well - to the wide range of views represented in Islamic politics, much of which is eminently rational. We might look at work like that of Prof. Jim Al-Khalili, presenter of the BBC's Science and Islam programmes, which explored the scientific advances in Islamic cultures between the 8th and 14th centuries without which European Enlightenment thinking could not have developed.

Open and informed debate about ideas is the last thing this government wants. Far better a blinkered electorate to follow their schoolboy dreams of regulated education and healthcare which might pay out good money to those with capital to invest in them - just happen to be most of the cabinet and their mates.

Actually universities don't provide quite such an open forum for debate as we would like to believe we do. I've heard incredulity expressed when a student said she wanted to develop an Islamic sociology. We inheritors of the thinking of Auguste Comte feel that one of the most important developments of the Enlightenment was the shift away from a religious dependency on The Word, or words in a particular text, as The Truth, towards reliance only on what we can observe and scientifically prove. Yet many would point to the 14th century (8th century AH) writer Ibn Khaldun, with his theoretical model of social conflict among Berber peoples in the Muqaddimah, as the earliest social theorist.

Francis Fukuyama, who famously declared the end of history, has more recently suggested that the West's primacy in world economics stems from its adoption of the scientific method and institutionalisation of this way of thinking through the network of universities. However others view the legacy of Enlightenment thought in a less positive light. Mark J. Smith, in his book The Challenge of the Social Sciences, points to a remarkable similarity between the way hypotheses are developed in post-Enlightenment science and ways thinking was done under the Church in Europe. There is a strong school of criticism of the iconic text of Enlightenment philosophy, René Descartes's Discours de la méthode which contains the famous statement: I think therefore I am. Many see this as a dangerous splitting of the body from the mind, since as part of his argument, Descartes dismisses feeling as a proof of existence. Not only this, some would argue that it leads to an ethos which splits all of the world into two: mind/body, man/woman, white/black (Cartesian dualism). This then leads the whole of Enlightenment thought down Manichean pathways. There is extensive feminist critique (e.g. by Ludmilla Jordanova) of the way in which science has depicted nature as, for example, a woman whose secrets should be torn from her in rape (Bacon). The recent tv series All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace discusses the ways in which racist scientific procedures led ultimately to tragedies like the genocide in Rwanda.

What then if we tried to move beyond the dichotomy of reason and unreason (emotions, religious faith, nature). Would that allow us to stop having to think about ourselves only in dichotomous reference to some Other? Perhaps then we could stop positioning Islam as one irrational, dangerous and enemy entity and understand that there are far more differences within Islam than there are between Enlightenment thinkers and Muslim believers.

|

| The Alhambra in Granada |

|

| Ahdaf Soueif pours tea in the West Bank |

|

|

| All Muslim rugby team at prayer |

No comments:

Post a Comment